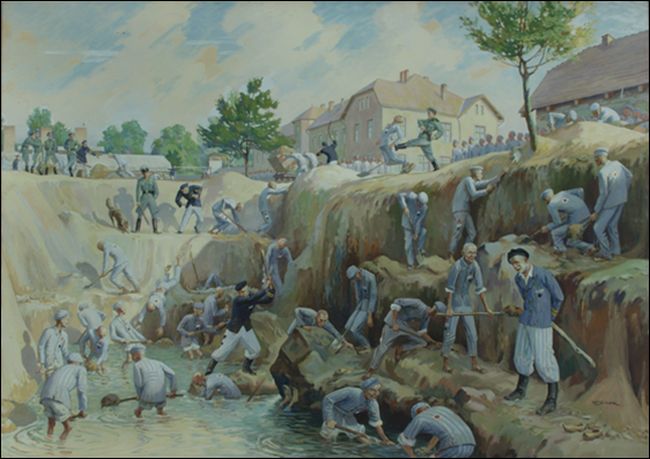

Although the first Jews were deported to the camp as early as in the summer of 1940, at that time they could not develop a resistance movement due to the especially brutal treatment and extreme mortality. In the first few months of operation of Auschwitz, all the Jews brought in transports together with Poles were separated at registration and sent directly to the penal company in Block 11. There they were commissioned for labour that required great exertion and murdered after a short time. The few documents preserved from the time prove that the Jewish inmates frequently tried to escape. Yet all attempts ended in failure. Some must have been acts of despair: hopeless attempts at avoiding the beatings of the Kapo, while others were provoked by SS guards who in return for ‘thwarting an escape’ received official praise in the commander’s orders, or a few days’ leave. The only traces of attempts of organised activity among the Jews can be found in the logbook of the bunker of Block 11: eight Jews from the penal company were incarcerated in detention cells, most probably for the purpose of investigation. After the completion of the investigation they were all murdered.