[...] The captured resettled Poles were mostly assigned to the SS labor camp in Auschwitz (Hydrierwerk) [here and then in the original, literally: SS- Arbeitslager in Auschwitz (Hydrierwerk); in fact, it is a sub-camp of Auschwitz Buna in Monowice. W.W.-M.], while a relatively small number of them were put at the disposal of the employment administration for dispatch to the Reich. Poles from those territories, who were not sent back to the Reich, were set up as peasants or settlers in the so-called integrated villages (Z-Dörfer), located between German settlements.

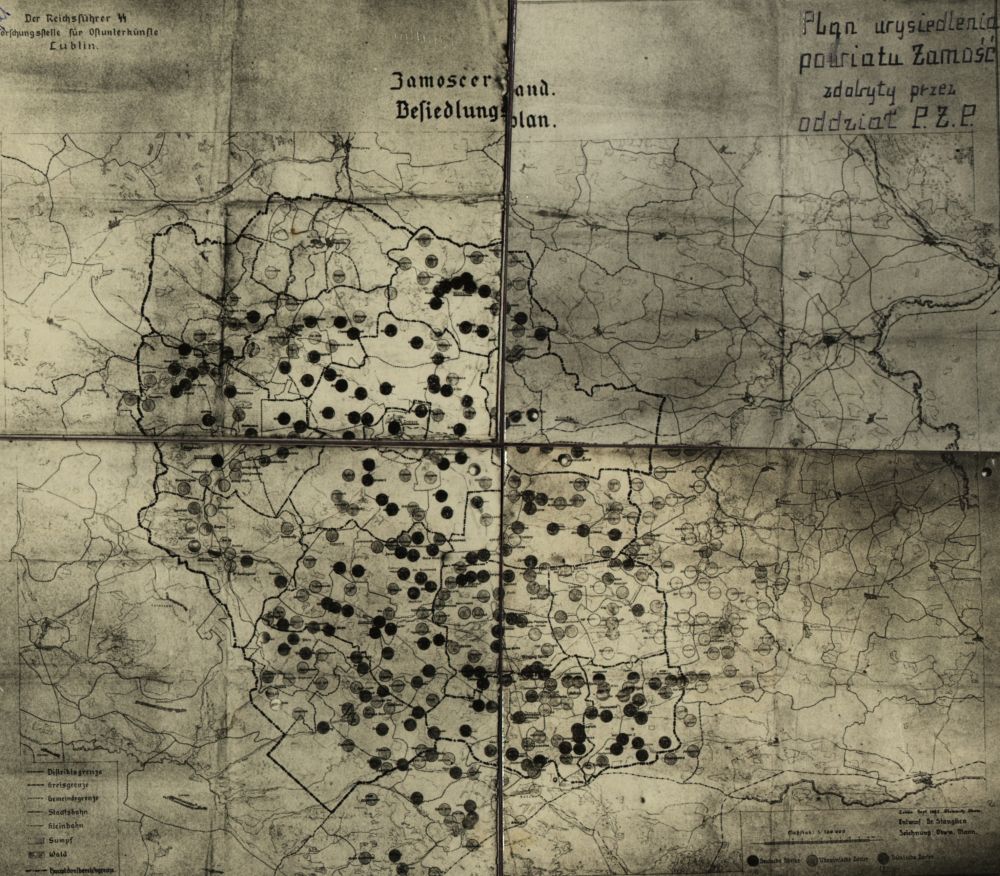

[...] The Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Nationhood offices (Reichskommissar für Festigung des deutschen Volkstums-RKF) carried out settlements and displacements on their own. [...] To supervise the resettlement, the SS and police commander employed 50 police officers and about 80 members of the special service who were detached from their daily important tasks in the district. Cooperation between the administration and the RKF offices was difficult, as the RKF offices did not provide the administration with comprehensive and sufficient information and kept their activities secret, even in relation to the relevant administrative factors. Thus, it was impossible, for example, to obtain an exact number of Poles displaced by the SS. As a result of many escapes of those troubled by resettlement, the action reportedly affected only about 25,000 people.

1. Uncertainty regarding life

Fear of being threatened like Jews or sent to a concentration camp.

2. Uncertainty regarding the family.

Separation of families, mothers from children.

3. Uncertainty regarding economic existence.

Contrary to the order of the Secretary of State Dr. Bühler of 7 October 42, no new living conditions were created for Poles, but in the most cases, they were sent to forced labor in Auschwitz. They lost their property almost completely.

1. The escape of the rural population

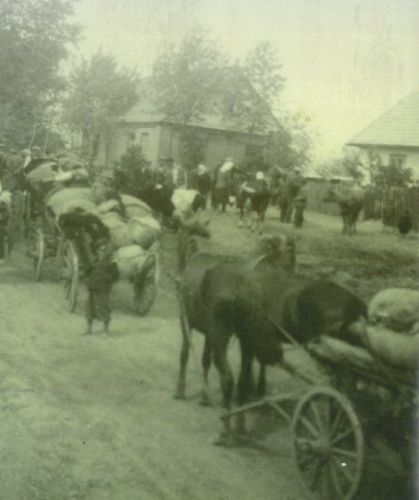

For reasons given in section II, the rural population, shortly after the start of resettlement, began to flee massively to escape the alleged danger threatening their lives and their families and to save at least some part of their property. The peasants fled under the cover of the night and fog on their carriages, took their families, part of their livestock, and above all cattle. They travelled using the back roads and tried, in most cases with a positive result, to reach the nearest partisan troops or neighboring counties, where they went to their relatives or friends. Since this escape was unplanned, the Zamojszczyzna and Hrubieszów districts were left empty and the last remains of property were stolen. Apart from the economic damage that still needs to be discussed, this escape made it very difficult to inhabit the villages that were intended for the Germans. In addition, it is striking that the police managed to displace only 25,000 Poles, while they counted on double that number. Tens of thousands managed to escape. On the other hand, cattle had already declined significantly as a result of slaughter and sales on the black market.

2. Uncertainty

It is understandable that a large proportion of the refugees who had nothing to lose anymore caused the reinforcement of the partisan movement in the south of the district. It is conspicuous that since December 1942, troops of several hundreds of people, including women and children, contributed to increasing anxiety in the area.

We can already talk about the popular movement, organised in a military manner. This movement entangled entire police forces in bloody battles, and even repeatedly repelled the attacks. However, the effective combating of the partisan units active in these areas cannot be stated due to the lack of sufficient force.

According to the reports submitted to me, from the beginning of December 1942 until now 37 new German settlers were murdered by bandits in their settlements, 16 others were injured. An especially tragic fact is that there were a number of women and children among the dead. These high losses primarily caused the attack on the village of Cieszyn (Skierbieszów municipality), 18 km northeast of Zamość. This village was attacked on the night of 25 to 26 and 43 by about 120 bandits. These bandits came on sleds, where they surrounded and set on fire one farmhouse after the other. During these fires and firefights, 30 German men, women and children lost their lives, while eight were injured. The attacking bandits were accompanied by women and children who looted houses during the fire. There is no doubt that there was a clear act of vengeance on the part of the expelled peasants. In the period from 9 to 28 December 1942, 125 buildings were burned down in the Zamość settlement area as a result of the bandits’ activity. All these events were not strange at all. It is self-evident that the peasant population, who thought that their lives and their families were in danger and knew that they would lose all their property resorted to such desperate acts. In any case, as a result of these displacements, the Polish peasants threatened by it, who until now were treated decently and constituted a positive and creative element, became bandits, political conspirators and an extremely dangerous element threatening security! The claim made by the RKF that the country’s security would improve significantly in the course of resettlement was wrong.

So far, there is no doubt that resettlement led to the greatest security threat since 1939.”

3. The agricultural economy

The assumption that sooner or later he would lose his land caused the Polish peasant, who so far performed the duties imposed on him by the German administration very well, to become deeply reluctant and to feel despair, which, simply, cannot remain without influence on the efficiency of his work. Thus, the deliveries of milk, butter and other agricultural products have already fallen significantly, especially in the Zamojszczyzna and Hrubieszów districts. In particular, the supply of milk in the county of Hrubieszów decreased significantly. Whereas in December 1942 2.5 million liters were delivered, the quantity sank in January that year to only 600,000 liters. This alarming drop of 75 % is truly noteworthy. The number of pigs in many municipalities of this county fell by 60 %, and the number of poultry by 90% because the peasant gets rid of and kills everything to avoid losing anything without compensation. [...]

The impact of this resettlement on harvesting and spring field work is particularly dangerous. The mere fact that there are empty villages is in stark contradiction to the requirements of war, and the administration cannot find a remedy for the lack the necessary equipment. Above all the total lack of seeds, blocked a rapid and complete launch of abandoned farms. According to the report of the governors in Zamość and Hrubieszów, there aren’t many seeds in the resettlement area because the refugees took them. There are also 100 horses needed in the Zamość district for the most necessary spring work. [...]

4. Other Effects

Because the inhabitants of the city of Zamość correctly assumed that the population of their city is supposed to be resettled, they also began to flee and took a lot of luggage with them. They returned from time to time to collect more home appliances. As a result, the production of the city of Zamość clearly failed and numerous shops and businesses became idle.

However, resettlement also entails severe difficulties in administrative work. It is incomprehensible that the offices of the RKF, despite the reluctance of the authorities, expel qualified forest workers and thus paralyze the activities of forest administrations which are particularly important for the purposes of war. Furthermore, the rural population fled with their horses or disposed of them. Thus, there is a serious crisis in the Zamojszczyzna and Hrubieszów districts when it comes to the transport of wood for war purposes.

Although this type of district is considered very desirable for colonisation by the Germans, this task cannot be undertaken at the moment due to catastrophic consequences. [...]

In these circumstances, I require the urgent and temporary cease of resettlement, which shall be also announced.

[...] If resettlement continues, I will under no circumstances be able to assume responsibility for future harvests and deliveries of crops.