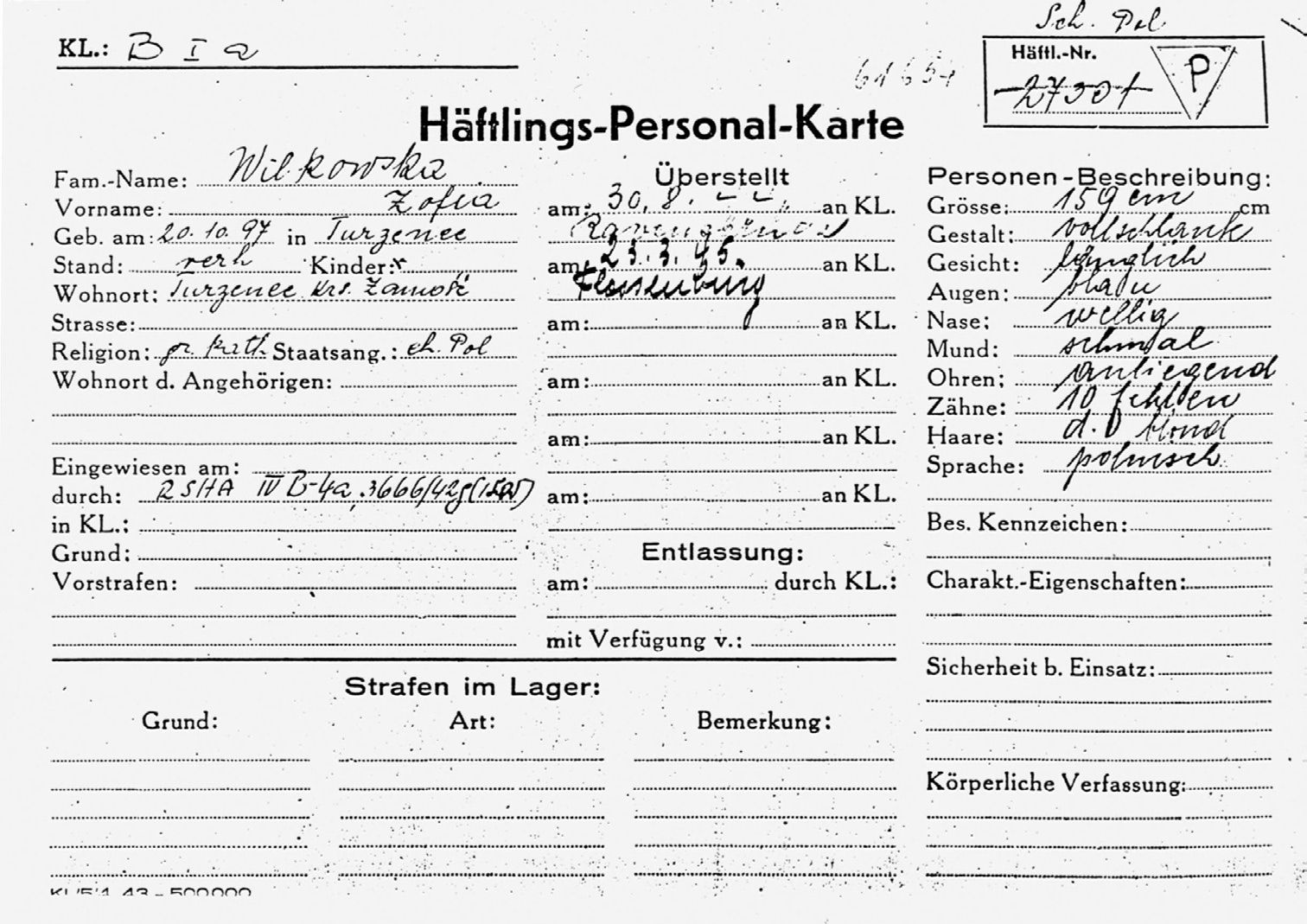

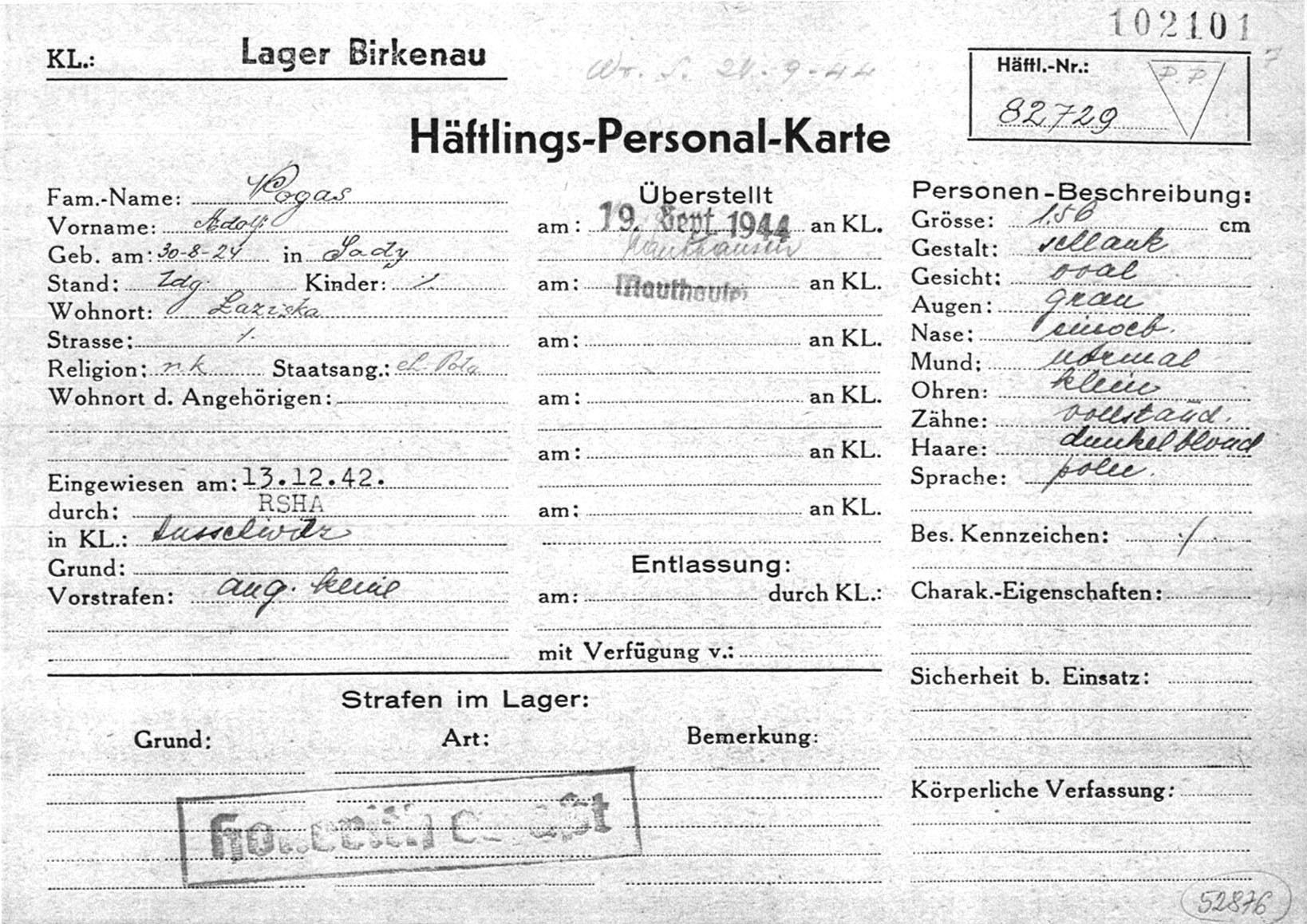

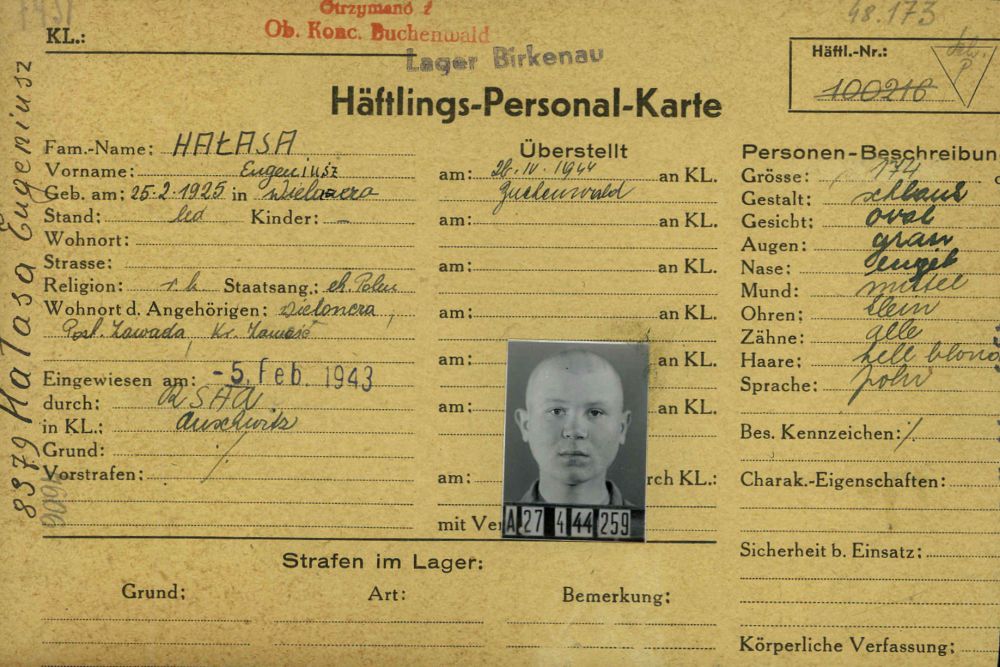

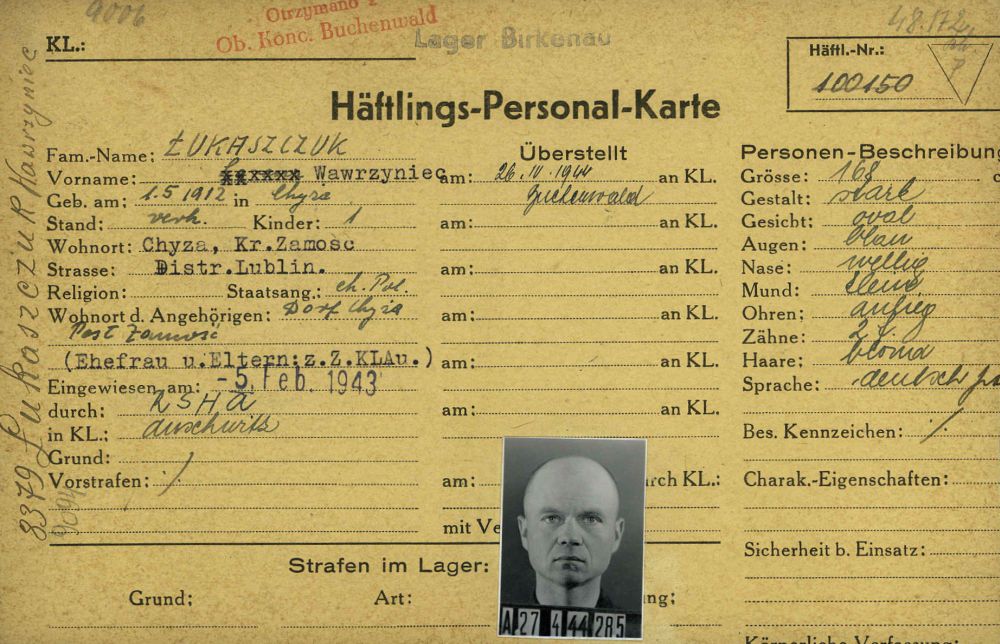

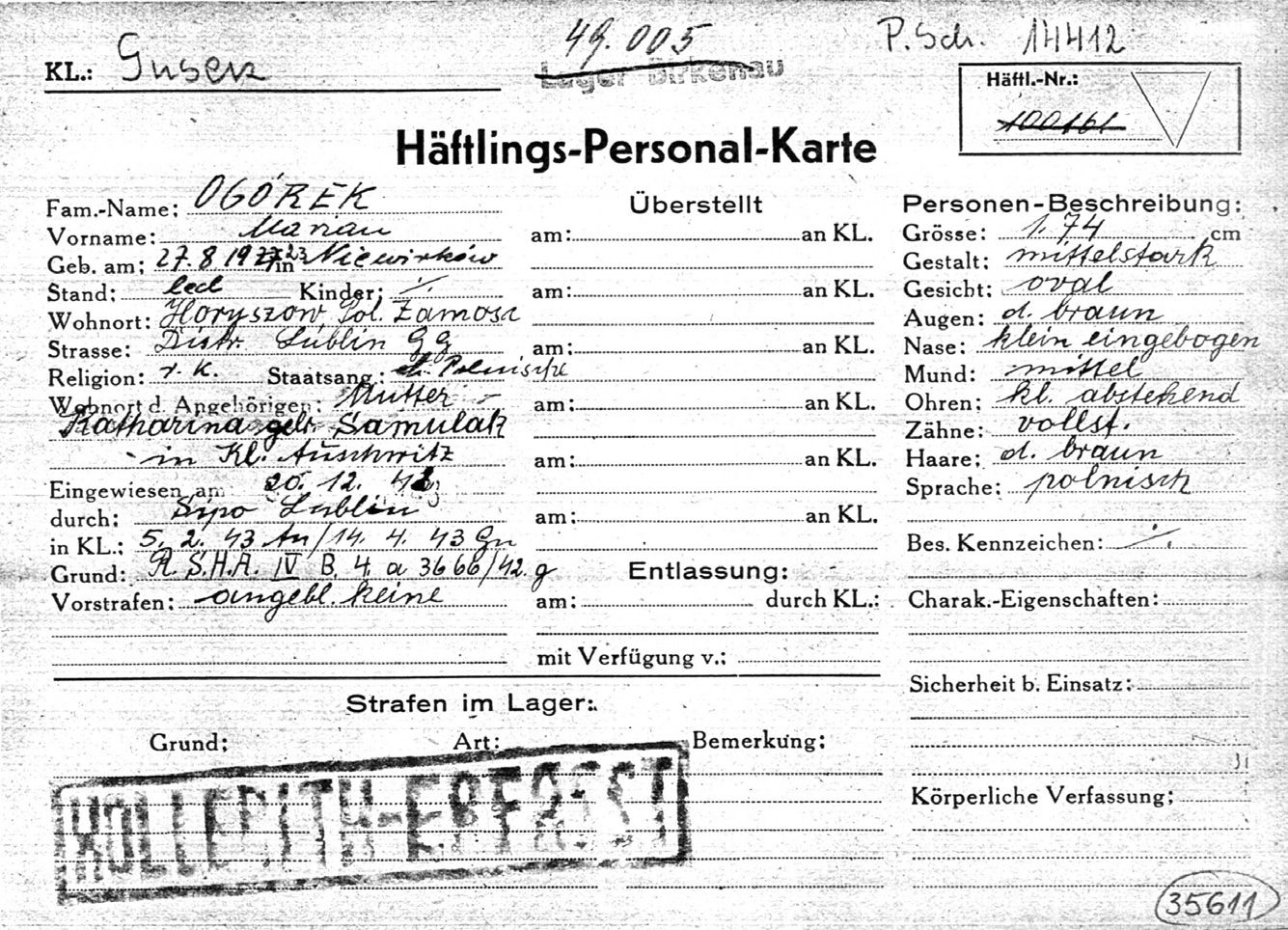

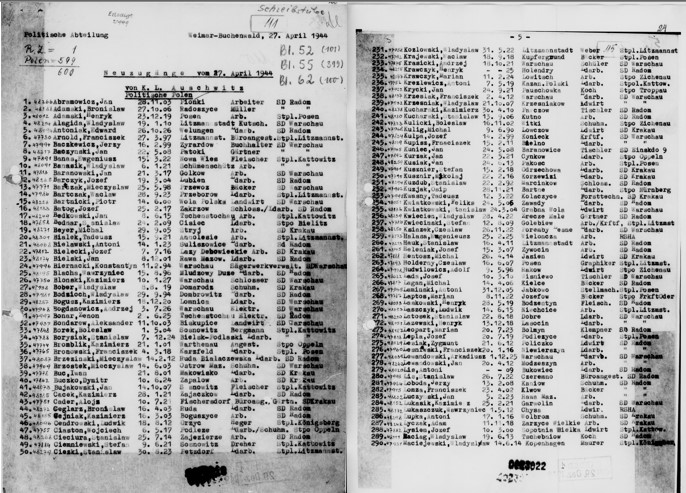

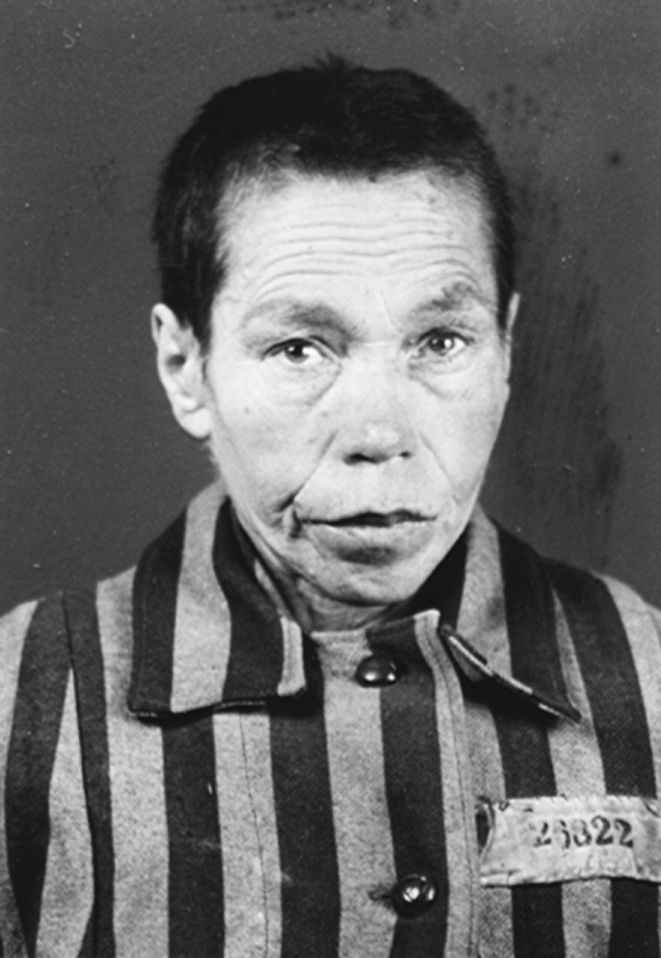

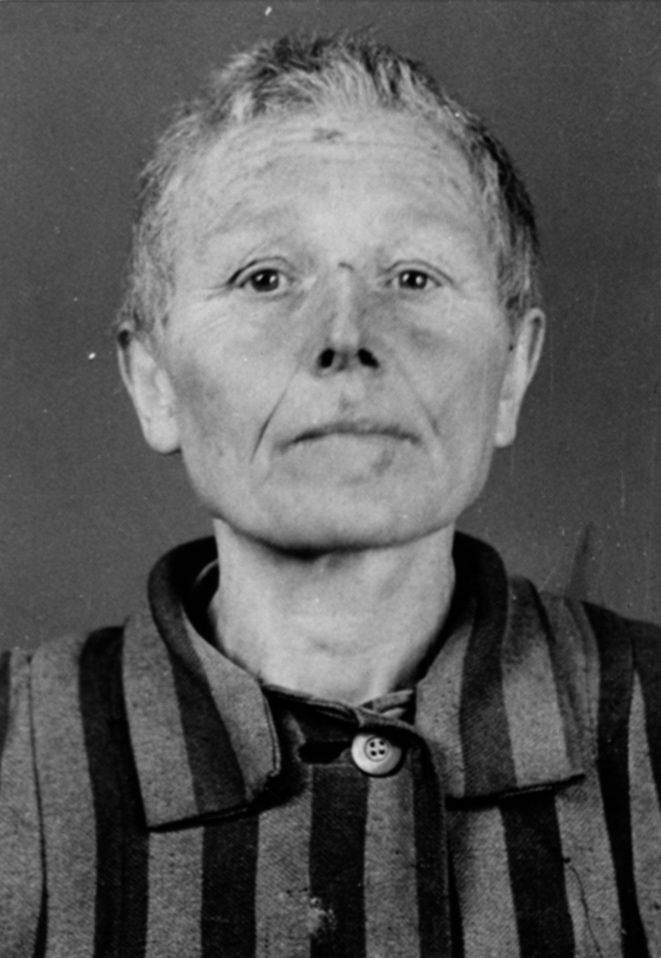

For people brought to Auschwitz from the displaced area of Zamojszczyzna, detention in the concentration camp was a shock, especially since they were generally accompanied by the belief that they would be taken to forced labor in the Reich. Although most of them were not charged or prosecuted, they were marked with red triangles, signifying political prisoners and from the first moments, they were treated with the same ruthlessness as other prisoners. The moment of disembarking from the wagons to the Birkenau ramp was accompanied by aggression from the SS: they were screaming and kicking the newcomers, beating them with the flasks of their rifles, and setting the dogs on them. Families were not allowed to reunite, women were brutally separated from men and set up in separate groups. Many men saw their mothers, wives and daughters for the last time. Many women were also doomed to never see their fathers, brothers or sons again.