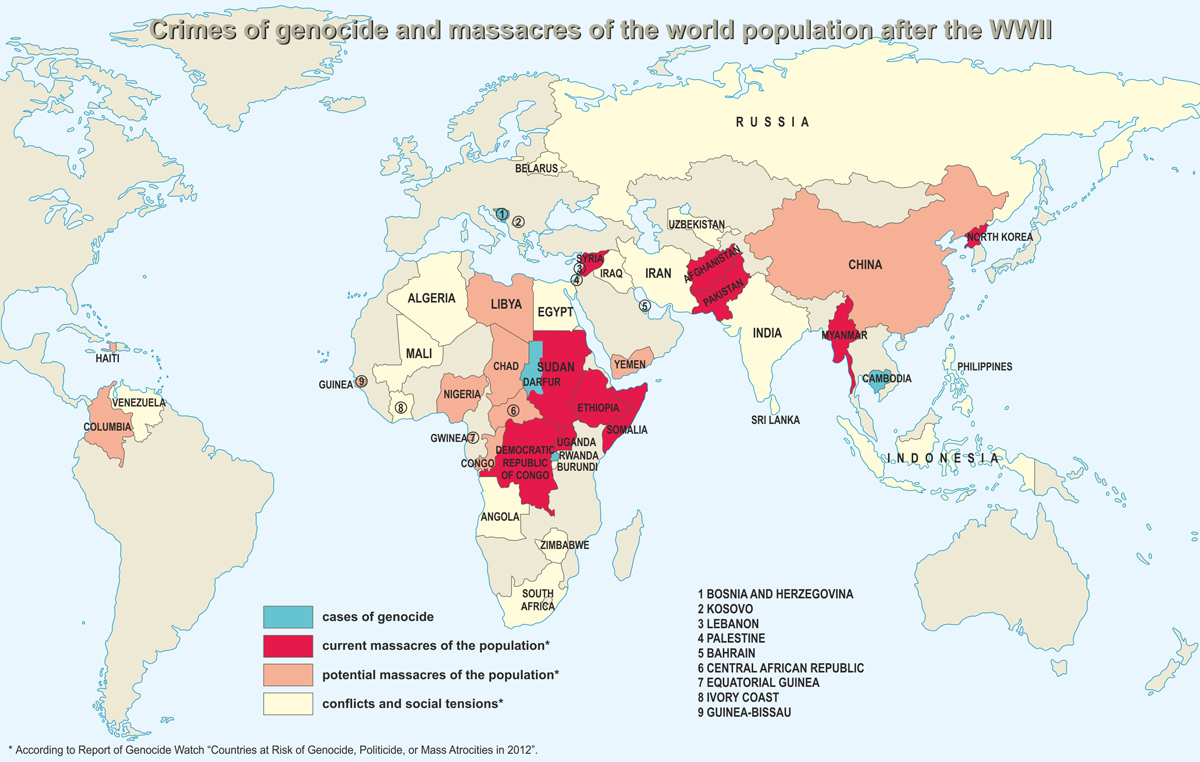

Hundreds of millions of people risk becoming victims of genocide and related acts of violence. These people live under the governments of political regimes that had and still have inherent propensities to commit mass murder. In some countries, for example in Sudan, the killing is ongoing. Elsewhere, such as in Rwanda, the killing has been very recent. And in other countries, including Kenya, the threat of mass murder seems very real—it almost hangs in the air. And in yet other places, despite visible signs, warning of imminent danger, mass slaughter might occur at any moment.

Our era, since the start of the 20th century, has been plagued by successive mass murders. They have occurred so frequently and collectively have such immense destructive power that the problem of genocide is worse than war. So far nations and governments have done little to prevent or stop the mass slaughter of people. Today the world clearly has no intention to end the greatest scourge of humankind. Evidence of this inadequacy is overwhelming. It can be found in Tibet, North Korea, former Yugoslavia, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, Rwanda, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Darfur. Individual people, institutions and governments in every region of the world—we all have the choice.

We can continue this gross negligence, which is based on three elements: avoiding a sober appraisal of the true nature of genocide; failing to admit that we could much more effectively protect hundreds of millions of lives and radically reduce the frequency of mass slaughter; and avoiding decisions to undertake actions based on this knowledge.

Or we can address this plague; understand its causes, nature and complexity, its range and systemic character; and next, based on this understanding, precisely shape institutions and policies that may save countless human lives and remove the mortal threat under which so many people live.

…

Genocide begins in human minds. For a certain type of political leader, and even for ordinary people it is easy to dream of eradicating an enemy from their own neighbourhood or nearest neighbourhood, or of living in a cleansed community free of human, social, cultural and political contamination, in a community radically remodelled according to some auspicious plan. However, in order to accept this sort of goal as a real opportunity, as something legitimate and feasible, the political arsenal has to include the possibility of eliminationism, and in the real world this requires an appropriate political context. This context must make possible such actions and thoughts, it must make one and the other feasible. …

The successive political and human catastrophes of our time have shown that genocidal and eliminationist policies are born in the minds of not only political leaders but also their supporters, it flows from their lips and drives their actions. The last hundred years have been the most marked by mass slaughter and eliminationism in human history, they have witnessed genocide, mass expulsions, extensive camp systems and mass rapes that for the first time have been brought to the awareness of the whole world and especially to the awareness of political leaders.