On 17 September 1939, the Red Army (USSR) entered Poland and occupied the country’s eastern borderlands (Kresy), including the provinces (voivodeships) of Wilno (Vilnius), Nowogródek, Polesie, Wołyń (Volhynia), Tarnopol, Stanisławów and part of the province of Lwów (Lviv). To understand the situation of the Jews under Soviet occupation, one first needs to take into account various factors peculiar to these territories, such as the region’s national diversity (before World War Two, these territories were inhabited by Poles, Ukrainians, Jews, Belarusians and Lithuanians), political, cultural and social structures, as well as its historical developments since Poland regained independence after the First World War.

During the Soviet occupation, the Jewish population in this region rose considerably on account of Jews fleeing from German repressions in the German-occupied regions of western and central Poland. Towards the end of 1939, the number of Jews in the eastern borderlands (Kresy) rose to over 1.5 million (whereas before the war it was around 1 million).

Rafał Wnuk, Za pierwszego Sowieta. Polska konspiracja na Kresach Wschodnich II Rzeczypospolitej (wrzesień 1939 – czerwiec 1941), Warsaw 2007.

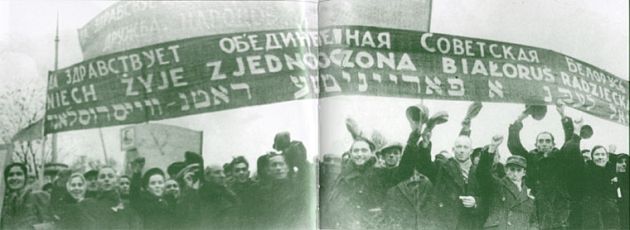

In the initial period of the occupation, immediately following the Red Army invasion of the eastern borderlands, the Soviet authorities started recruiting locals to a new (provisional) administration, and in doing so showed clear favouritism towards the national minorities. For Ukrainians, Belarusians or Jews living in these areas this meant rapid, though basically nominal, social advancement. Some of them greeted the Red Army with sympathy. Soviet propaganda presented the invasion as a measure to bring ‘freedom, equality and justice to the national minority masses oppressed by the Polish Sanacja regime.’ Some Jews, who before the war had been active in the communist movement, openly supported the new communist authorities. However, it should be remembered that the attitude of the Jews was diverse and conditioned by factors, such as, financial status, political views and education. Many Jews, especially orthodox ones, feared Soviet ideological hostility towards religion. Others were apprehensive, remembering the pogroms inspired by the tsarist government or the more recent Stalinist purges and political murders, which also affected many Jews. Moreover, there was fear that property would be confiscated.

From the outset, the Soviet authorities were hostile towards ‘class enemies’, like intelligentsia, priests, owners of estates, workplaces or factories, state officials (including railway workers, foresters and policemen), regardless of nationality or religious beliefs. In the eastern borderlands the largest group of people considered as ‘class enemy’ were primarily better educated or wealthy Poles, but also Jews. They were the major victims of Soviet repressions and violence. Polish state property and larger private estates were confiscated by the Soviet state. Soon followed a wave of detentions of members of the Polish intelligentsia accused of organising and supporting unground resistance against the Soviet Union.

In face of the repressions imposed on Poles in the eastern borderlands, the initial support for the Soviet occupation regime by some of the Jews considerably contributed to increase of anti-Semitism, already rooted in the żydokomuna (commie-Jew) stereotype, and helped to spread the false conviction that nearly all Jews collaborated with the Soviet occupant.

In order to ‘legalise’ their seizure of eastern Poland, the Soviet authorities organised the People’s Assemblies of Western Belarus and Western Ukraine and subsequently the newly elected assembly members formally request the Soviet government permission for their countries to join the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which naturally soon happened. This opened the way to change the laws and nationalise Polish state and private property leading effectively to further repressions against the inhabitants. The worst of ones were forced deportations deep into the Soviet interior. According to estimates, of the Polish citizens forcibly deported to the Soviet interior in the years 1939‒1941 around 52 per cent were Poles, but 30 per cent were also Jews, whereas the remaining were Belarusians and Ukrainians. This means that the percentage of deported Jews considerably exceeded their percentage as pre-war inhabitants of the eastern borderlands (Kresy). This contradicts the opinion that the Soviet authorities treated Jews better than Poles. Also, worth mentioning is the fate of Polish prisoners of war, the officers and NCOs murdered by NKVD in places like Katyń, because among them there were also many Polish soldiers of Jewish descent.

As at the beginning of 1940 the communist authorities started forcing inhabitants to accept Soviet citizenship, some Jews applied to be allowed to return to the General Government. As they returned to German-occupied Poland, they were soon placed in ghettos and eventually murdered in extermination camps. Those who remained in the Soviet-occupied territories lived in relative safety up until the German invasion of the USSR in June 1941. The German attacking forces were followed by special Einsatzgruppen units, assigned the task of murdering the Jewish inhabitants of the newly conquered territories. Most of the Jews deported to the Soviet interior survived the war.