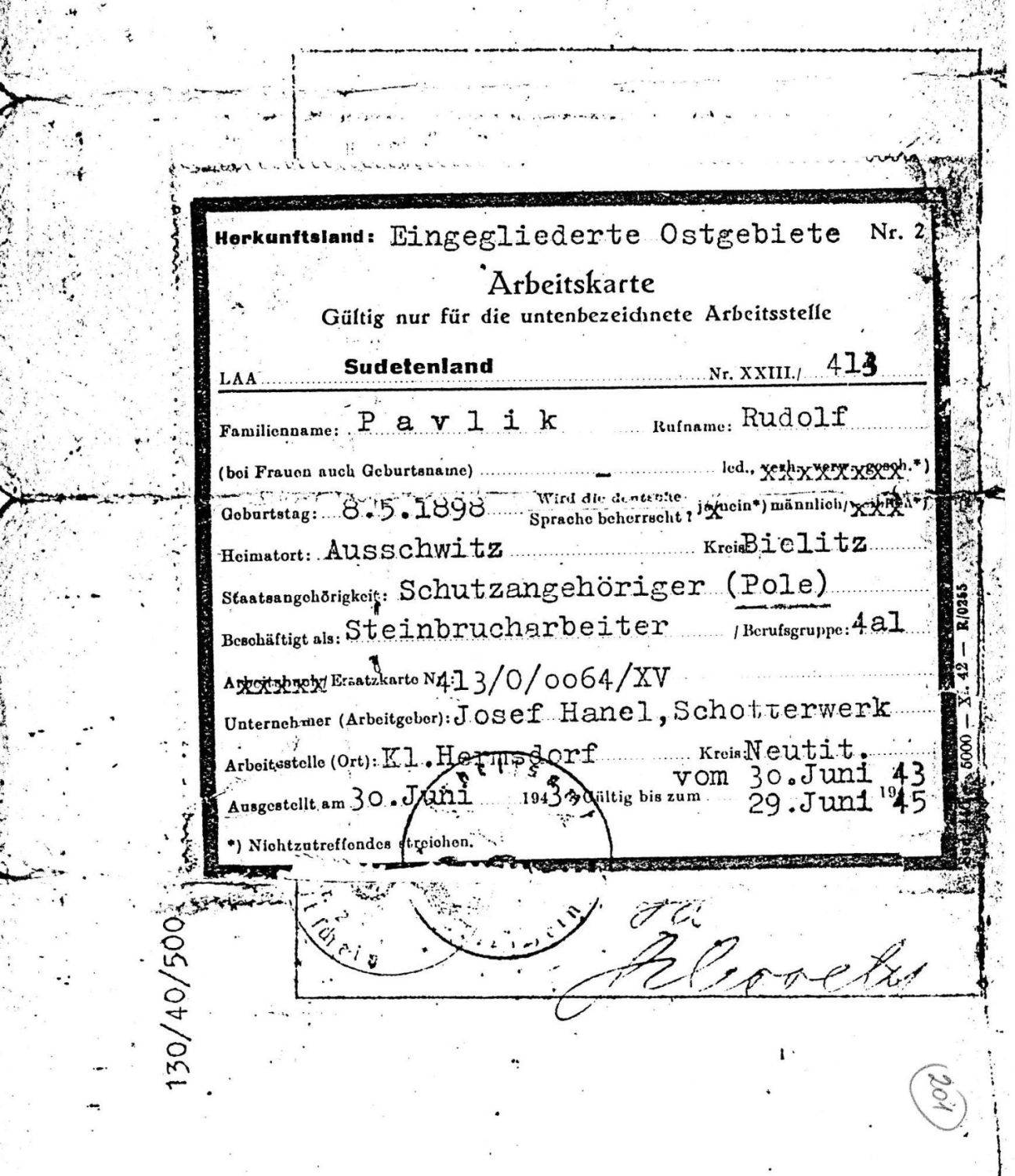

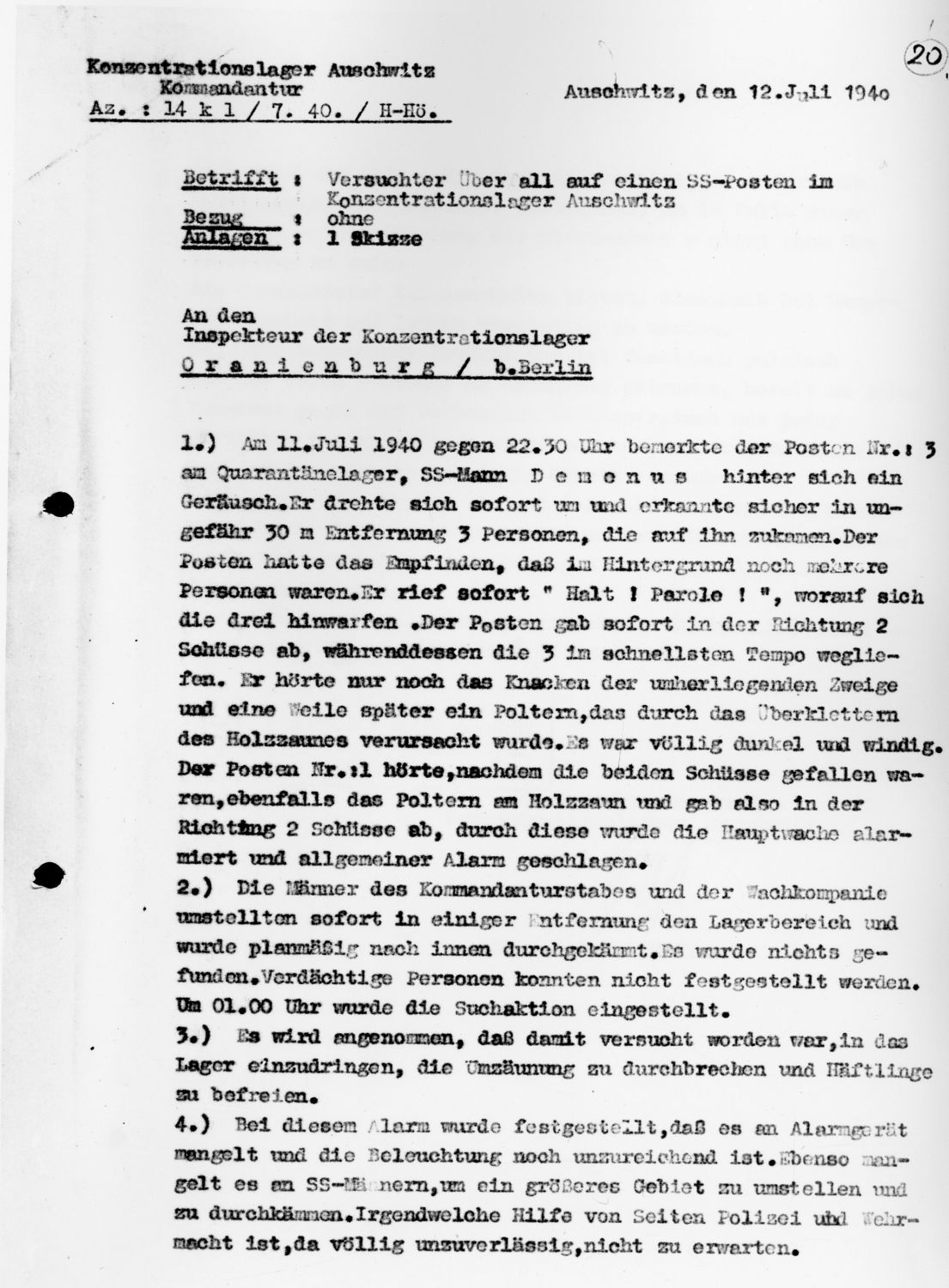

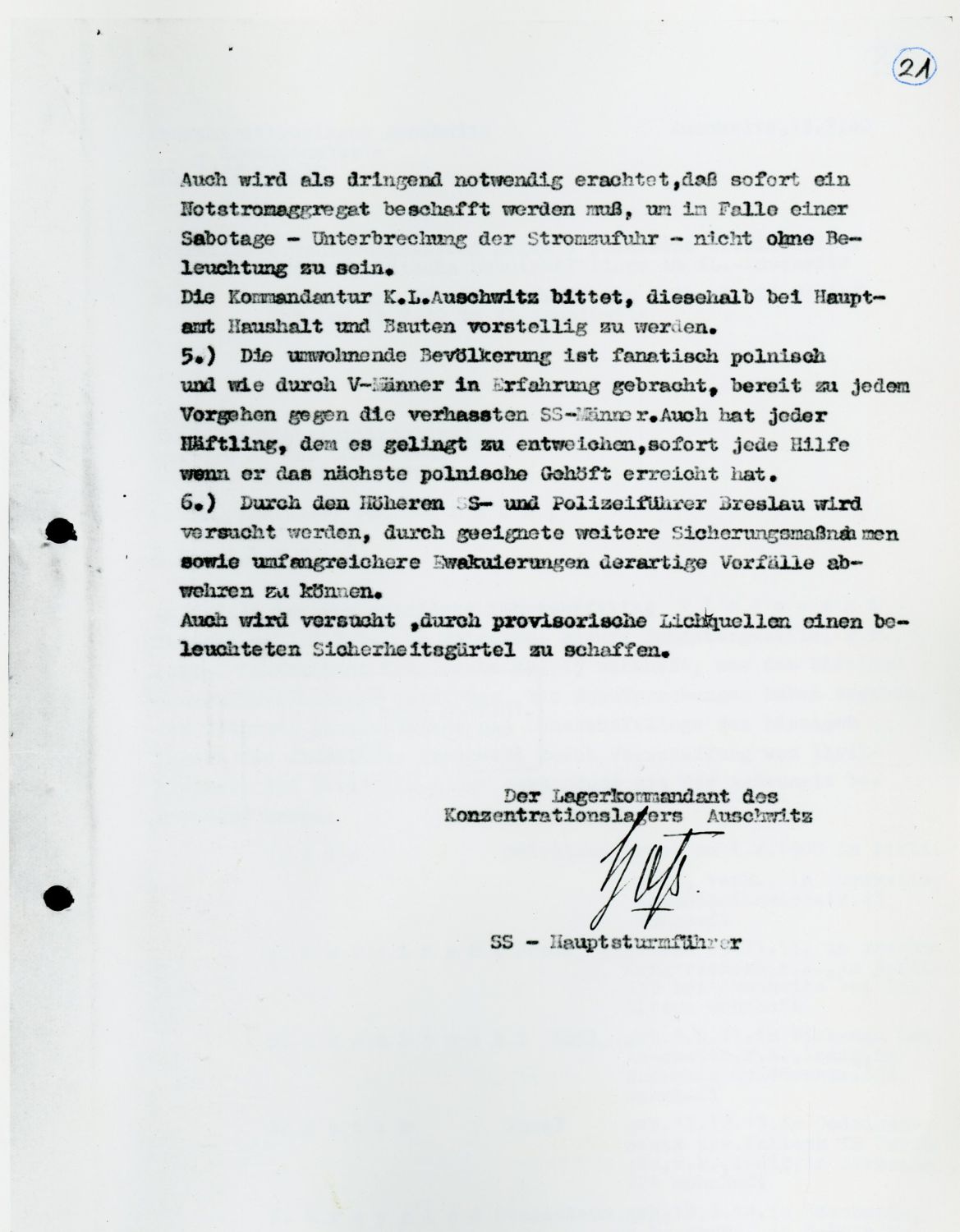

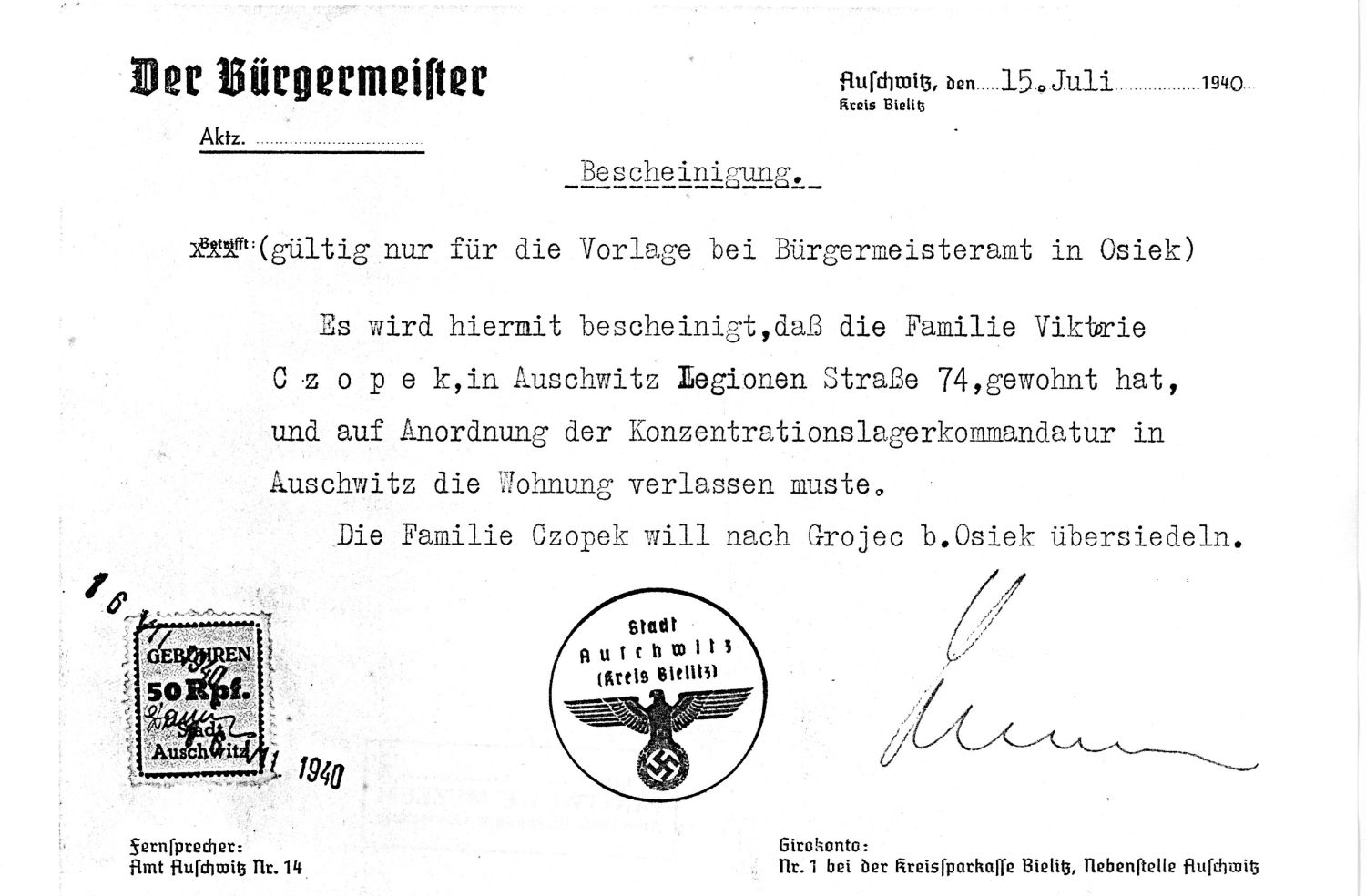

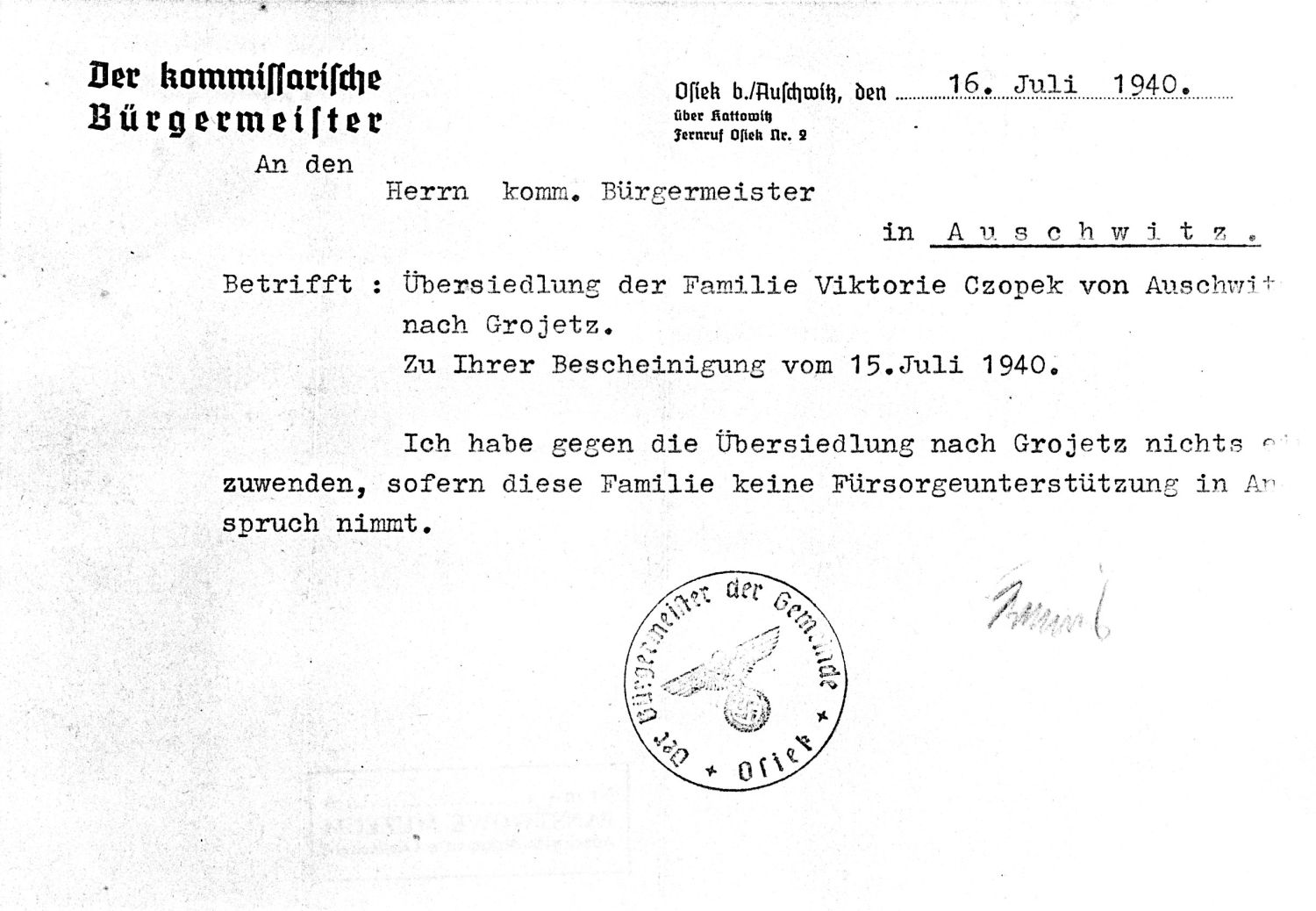

On 8th July 1940, in accordance with the summons, my husband Rudolf and I went to the hall at the house of the Wysogląd family. Similarly summoned to go there on that day there were the residents of the houses near the camp. In that hall, there were around a hundred people. The building was surrounded by Germans in light brown uniforms. After a long wait, some employment exchange (Arbeitsamt) officials from [Nový] Jičin in the Sudety [Sudetenland] entered the hall. These officials, standing on a platform or stage, called out the names of people from the list. Our names were also on that list. We were informed that we were being evicted and that we were going to be taken to do forced labour at a place called Neu Jistic [Neutitschein] in the Sudety. Here, I would like to note that entire families were deported to do forced labour.

On hearing the news that they were being deported, the people started to panic, cry and lament. To intimidate and silence them, the Germans surrounding the building fired their guns into the air. The men were loaded into the trucks and driven to the camp, whereas the women were allowed to return to their homes escorted by the guards. Together with my sister-in-law – also Timmel – we were driven to our home in the car of an SS officer from the camp. Before the meeting, I had prepared lunch. But I was not allowed to eat it or take any food with me. All they would let me take was some underwear, ration cards and money. Next, I was also taken by car to the camp, where I joined my husband. That same day, in the evening, we were loaded into the trucks and transported to Zauchtel [Suchdol nad Odrou] in the Sudety. … In the morning, next day … local farmers – Bauers – arrived. They selected families to work on their farms.

My husband was sent to work at a brickyard in Kunewald [Kunin]. We stayed there until the end of October 1940. Thanks to the intervention of the director of the [zinc] mill, who appealed on behalf of my husband, we were discharged and allowed to return to Oświęcim. Our house was rebuilt and converted into a Führerheim – a canteen for SS officers from the camp.