In 1940, the Germans started deporting the Christians, but they left the Jews in relative peace. Of course, there was the so-called Judenrat, who managed Jewish affairs the way the Germans told them to. Already in 1939, some 350 young Jews went to work in the barracks where now there is the Museum. I myself worked at the barracks where the Podhale Regiment horses stood. Before the war, I also worked in the so-called “tabaku” [snuff] warehouse. I knew the whole area, because before the war, we had … form the side of Mały Rynek (the Small Market Square). And I went to the warehouse for cigarettes and rectified spirit. Also, when the Germans were repairing the bridge over the Sola River, they were always able to commandeer some people to work on the bridge.

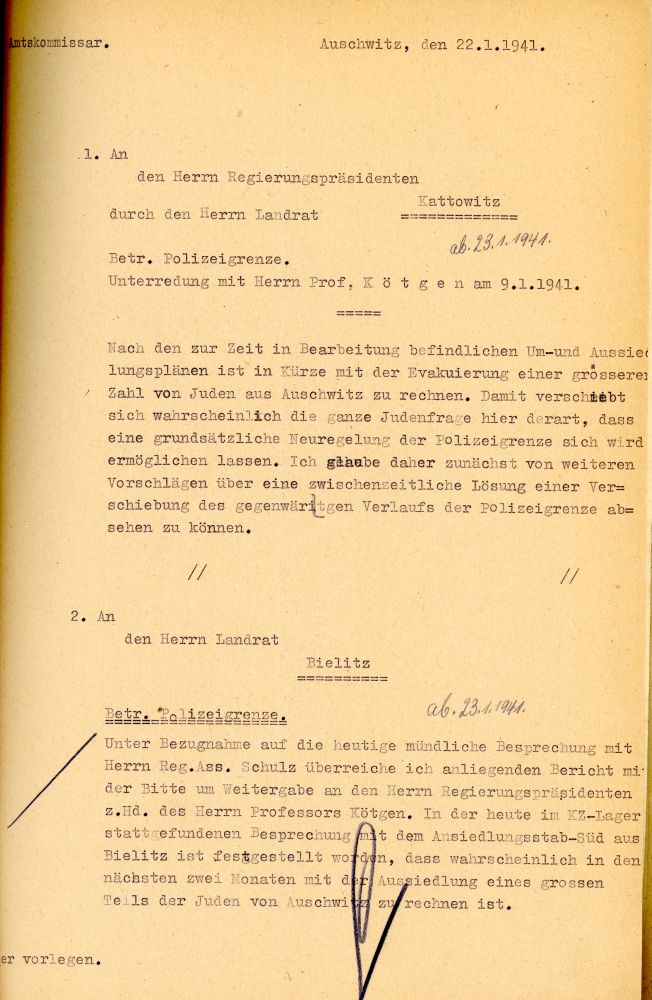

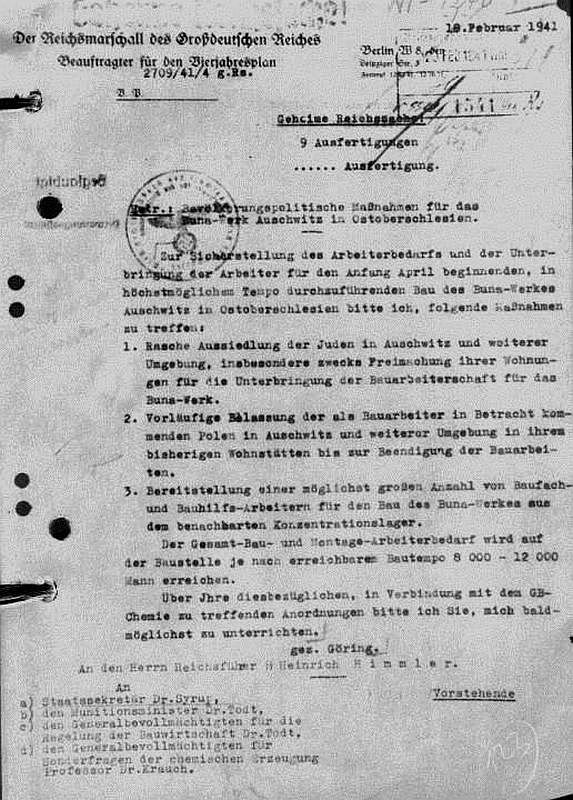

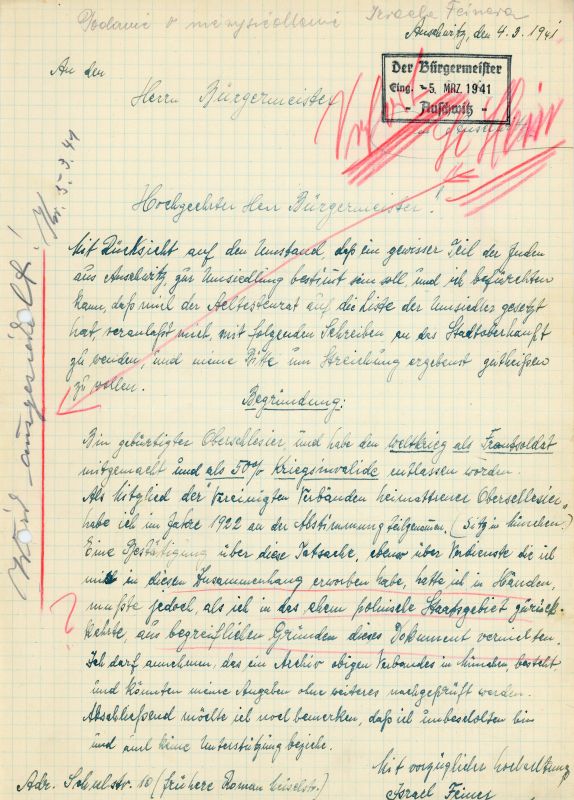

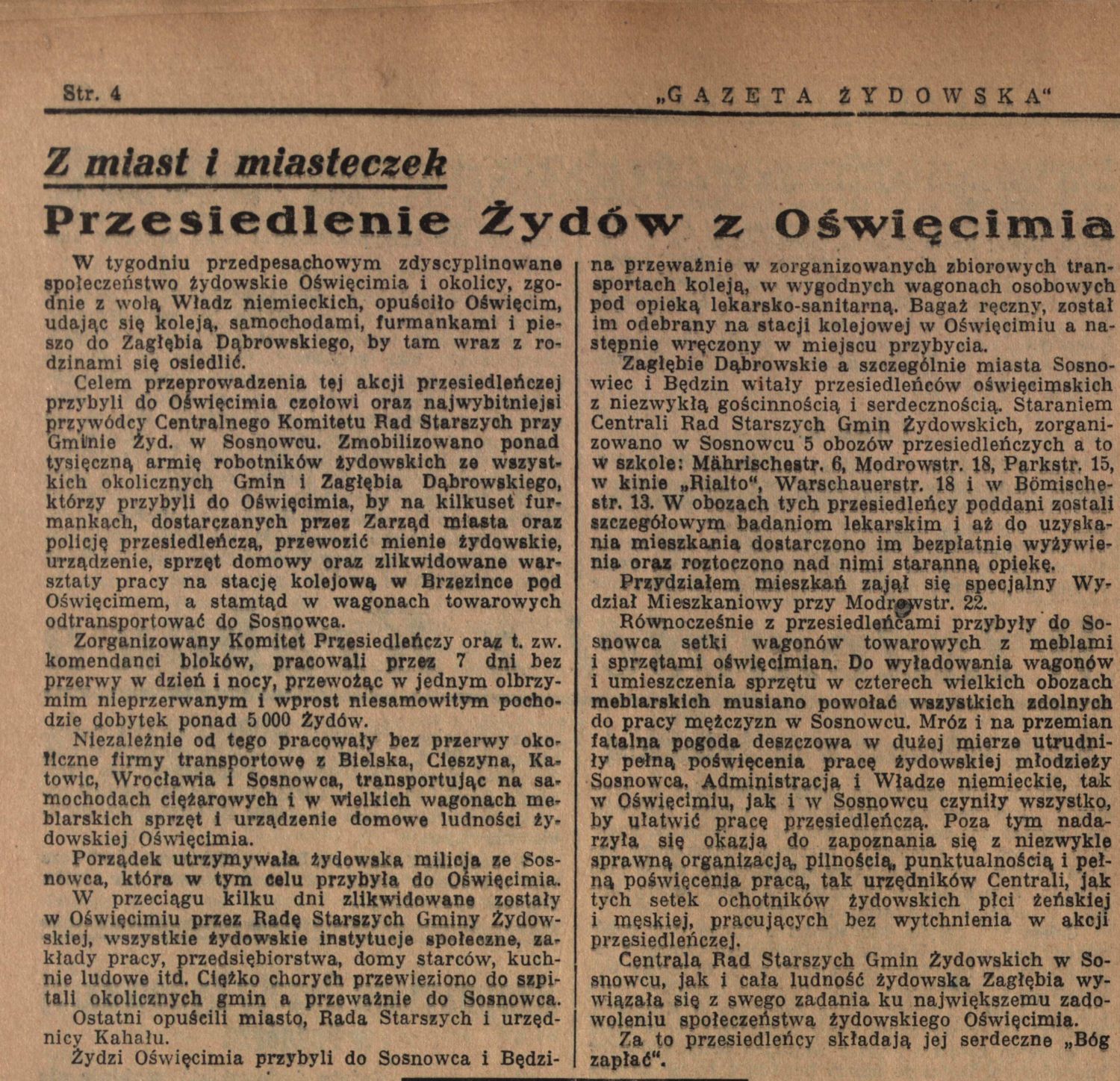

It began more or less at the end of 1940, posters were put up with the following message: “Alle Juden nach Palestyna [Palästina] fahren wollen, sollen sich beim Judenrat melden” – which means “All Jews wishing to go to Palestine must register at the Judenrat”. Of course, everyone wanted to escape – and that is how they obtained a list of all the people. We allowed ourselves to be fooled. At the start of March, notification was given that, during that month, we would have to leave Oświęcim. They granted us permission to take everything. There were three cities to choose from: Sosnowiec, Będzin and Chrzanów. My father said: “We’ll go to Chrzanów.” Those who went to Sosnowiec and Będzin, travelled on a special train. We were picked up by a peasant from Polanki, who took us in his cart to Chrzanów. His operation did come as a surprise, one way or another, we were helpless. I never found out who moved into our house and home.

When we arrived in Chrzanów, they gave us a single room, somewhere in a hull. I do not remember anything about the ration cards. I was 15 when the war broke out and I do not remember any case of anyone not conforming, that is if they wanted to live. On 8th May 1941, I was apprehended in Chrzanów and sent to the camps. The last one was Waldenburg concentration camp (No. 64242).

On 18th-19th February 1943, the rest of my family was sent from Chrzanów straight to a gas chamber in Auschwitz. Karol’s only sister survived in a camp in the Sudetenland (the Sudety Mountains).

Before the war, everyone in Oświęcim knew the Hennenberg family. My grandfather, Naftali Bochner, had a small house in Mały Rynek, he was a city councillor and a chief member of the Qahal.”